Attention (1): A Bunch of Asparagus

This is the preface to a series of essays about ‘Attention’ in our world, including our schools.

Still Life with Asparagus, Adriaen Coorte, 1697

The Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam is one of the world’s great repositories of European artistic achievement. Hordes of visitors mill around checking out masterpieces by Vermeer, Van Gogh and, especially, Rembrandt, whose Night Watch dominates the magnificent Gallery of Honour.

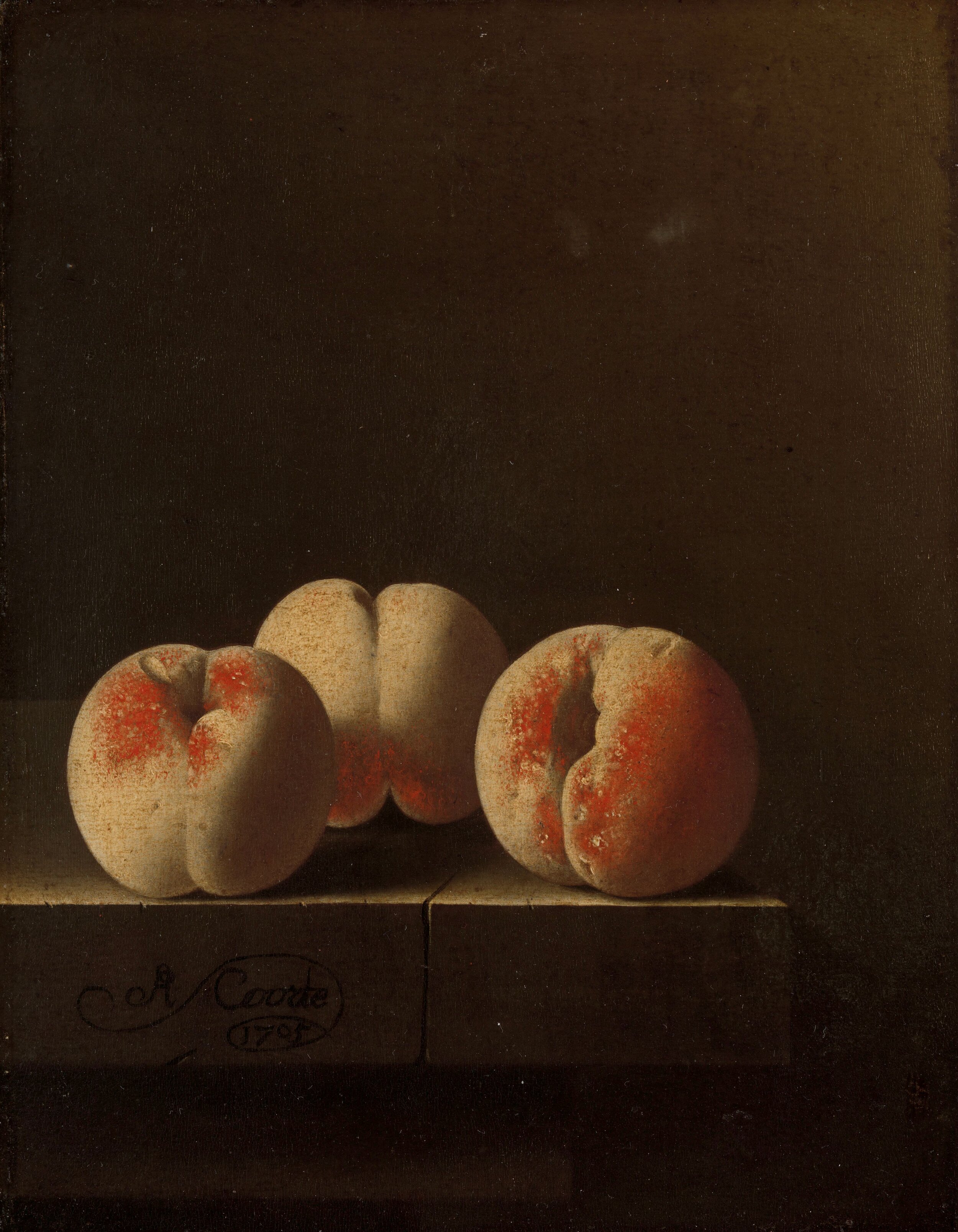

Last summer on a visit to the city I once again paid due obeisance to those works, and then wandered off aimlessly into the side-rooms and minor galleries. There, I was arrested by a painting I had never seen before, by a painter whose name was new to me. It was a still life of a bunch of asparagus, dated 1697. Beside it was a group of four other similar pieces, also by Adriaen Coorte (c. 1665-1707/10).

You need to see the thing itself: it is difficult to gauge the quality of ‘Still Life with Asparagus’ via a digital reproduction, let alone a description of it, though let me try.

About 20 spears of asparagus (a guess - we can’t see the depth of the bunch) are tied together by some twisting russet-coloured string. Poised on a cracked stone tablet, they loom out of a richly dark background. Coorte’s skill is seen particularly on the left-hand side, where some of the spear-ends overshoot the others, somehow semi-transparent against the blackness. They are delicate and luminescent, presenting themselves confidently to the viewer as objects worthy of our sustained attention. There is nothing spectacular or ‘significant’ here: no battle, no important burghers, just some vegetables and fruit. In the words of the Rijksmuseum:

through their simple subjects – asparagus or berries – these modest paintings stand out in stark contrast to the sumptuous still lifes that were in fashion at the time. While the aim of those works was to present a superabundance of costly objects and foodstuffs, here attention is focused on the refined rendering of a single vegetable.

Attention was indeed what I gave this painting, and its companions (still lifes of strawberries, peaches, gooseberries and apricots) for a long time. Look at them in the gallery at the bottom of this post. These works embody attention: this is an artist whose focus on these objects was so intense that over 300 years later his creations still command our gaze. They come to us from a different world, and present us with images of what attention might be, in a world in which attention seems to be under increasingly severe threat.

The short essays that will follow in this series examine this idea, particularly in reading and in education. In what ways is ‘attention’ being challenged? How might we address this? What does this mean for our schools? The journey will take in Maryanne Wolf, childhood reading, Robert Caro, Thomas Newkirk, Elizabeth Bishop, more poetry, my car’s dashboard, Arthur Miller, lots of technology, some cognitive science and, naturally, Shakespeare.

Next: thoughts on Maryanne Wolf’s Reader, Come Home: the reading brain in a digital world.