'Elizabeth Bishop' by Jonathan F.S. Post

Elizabeth Bishop is well-suited to OUP’s series of ‘Very Short Introductions’. Jonathan F.S. Post’s book is under 150 short pages, and Colm Tóibín’s fine On Elizabeth Bishop (2015) in the Princeton University Press is not much longer. As Post points out, the whole oeuvre ‘represents an astonishingly small number of published poems - about 90 in all’, mostly found in just four individual books. And the last one, Geography III, has a mere ten poems. My Library of America edition of Poems, Prose and Letters is almost 1000 pages long, but even with the uncollected poems, the prose forms most of that volume.

But what poems, and what a life’s achievement! As Post states,

No 20th century poet has gone so far with so little, has made such a virtue out of scarcity.

It is just that carefulness, precision and indeed modesty that make Bishop one of the most attractive poets of the last 100 years. In Post’s words, she tended to ‘the diminution of the visionary moment’, a stance which is all the more consoling in our noisy pontificating contemporary culture.

For those teaching the Irish Leaving Certificate, that selection of poems features prominently here, with sections on ‘Sestina’, ‘Filling Station’, ‘First Death in Nova Scotia’, ‘The Armadillo’, ‘In the Waiting Room’, and ‘Questions of Travel’. Beyond those poems there is extended analysis of, among others, ‘Roosters’, ‘Brazil, January 1, 1502’, the famous villanelle ‘One Art’, that masterpiece of loneliness ‘Crusoe in England’, ‘Santarém’ and of course ‘the most charming’ ‘The Moose’.

Chapter 2 examines ‘Formal Matters’, covering the extensive range of forms (including that sestina, the villanelle, the ballad the sonnet, the ballad and more) Bishop used despite the smallness of the oeuvre. As Post writes,

The one law she seems to have observed was never to repeat herself.

and a key element of her approach was

supreme valuation of formal variety as a means to singularity.

Her painting, and the extent to which her poems are painterly, are looked at in Chapter 4. She wrote that she aspired to Vermeer, though I think that her poems never settle into the profound calmness of the great Dutch painter; restlessness and uncertainty are never far from the surface, and she never took anything for granted. Post writes that ‘The Fish’ is

the most Dutch of her poems, a near still-life featuring even in a microscopic close-up of the fish’s glassy and ‘yellowed’ eye.

Though it never is a still life (it might have become one, the fish getting perilously close to death through the trailing lines of the long poem), and at the end the fish swims off, slipping away from Bishop’s painterly eye to resume its life.

In the final chapters, Jonathan Post looks at Bishop’s love life and the late travel poems. On the former, that marvellous erotic poem ‘The Shampoo’ is discussed in detail in a recent podcast by Kamran Javadizadeh and Lindsay Turner.

Despite its ‘very short’ nature, this overview of Bishop’s life and works feels comprehensive, mostly due to the clarity and concision of Jonathan Post’s analysis. Listen to an interview of Professor Post by Mark Bauerlein in the player at the bottom.

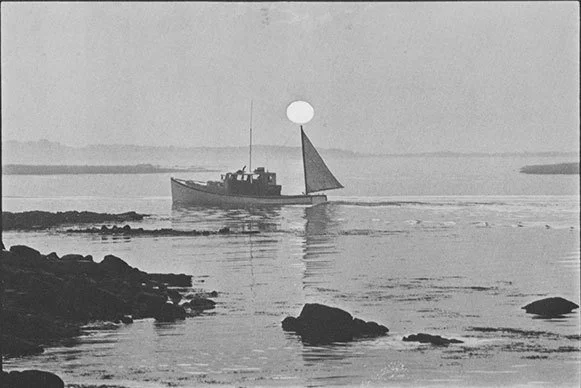

First, below is a black-and-white version of a photograph taken by B.A. (Tony) King in 1977, which Bishop commented on in a postcard to her friend Millicent Pettit in the last year of her life. Have a look at it and consider what Bishop’s criticism of it was: this opens Chapter 1 of Jonathan Post’s book and is the keynote to his demonstration of how the poet says ‘much in little’.