On Victoria Kennefick's 'Egg/Shell'

Eat or We Both Starve was the startling title of Victoria Kennefick’s first poetry collection, published three years ago. It properly received much attention, since the voice was immediately fresh, adept, challenging.

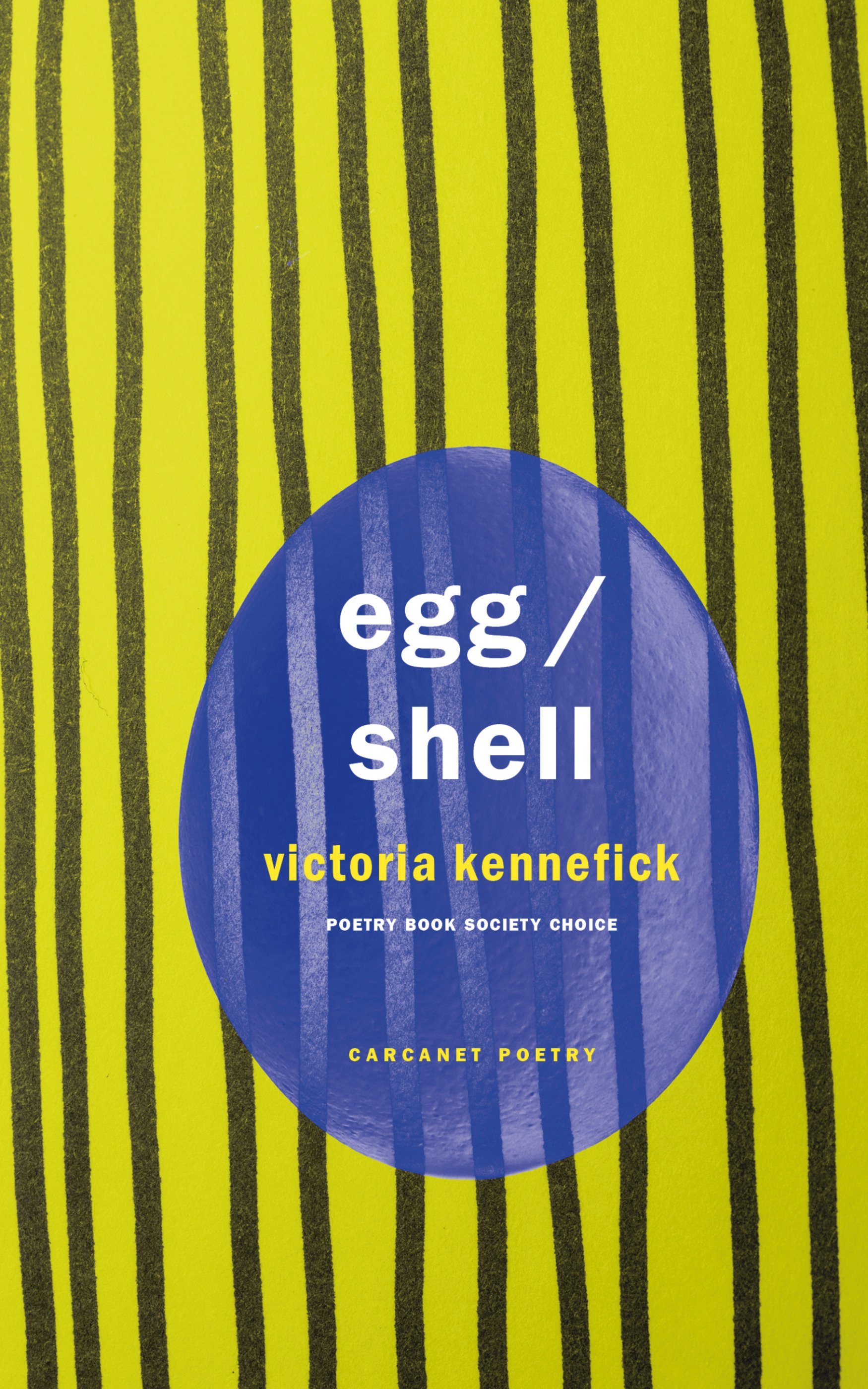

Now comes Egg/Shell, a capacious collection of over 100 pages with a wide range of approaches to recurring themes, especially to do with the female body. The title draws our attention to fragility, the slash between the two words a thin dividing line between the two parts of the book, and indeed so much of that fragility is explored in the poems. There is the line between life and death (especially miscarriage), and between male and female (a transition features in the second part). Victoria Kennefick approaches these difficult and painful topics in a great variety of ways: shaped poems, prose poetry, an ode, single-line works, even one of those exasperating verification captchas that we all hate (‘Select all images with crosswalks’). When I came across an Erratum slip for a couplet on page 80 I half-thought this might be another conscious experiment with form, especially since on page 81 there is ‘Vault of Obsolete Pronouns and Defunct Descriptors’, a poem which consists of three words - ‘husband’, ‘he’, and ‘his’ - repeatedly struck through. Her poem ‘Special Topics in Commemoration Studies: the Kerry Archives’, which I heard at a reading in the UCD Festival last year, addresses the complexities of local history through many forms, including ‘Group work for Secondary School History Students to promote co-operative learning when studying the Irish Civil War.’

One of the distinctive elements of Kennefick’s writing is her lightness of touch, a level of humour and sometimes even self-mockery when she addresses difficult personal topics. Another is her expertise with endings, often resonant and thought-provoking. Since I need to spend more time with the collection in the coming weeks to appreciate it more deeply, for the moment let me end with directing you to ‘Census Night Poem’, more conventional in form than some of the other poems, but savagely moving in its raw directness. It starts:

I cry every time. I am so small.

and, thinking about dead relatives, ends

Is there a box for grief?