Recommendation Round-Up

Some brief book-recommendations: these were in The Fortnightly in the first six months of 2022, but I didn’t get around to comment on them in longer form for my main book page.

I Heard What You Said: a black teacher, a white system, a revolution in education by Jeffrey Boakye

I'm drawn to books by teachers about their teaching experience, for obvious reasons. In his new book English teacher Jeffrey Boakye gives an angle I haven't come across before, narrating his own story as a black man in an overwhelmingly white education system (not as overwhelmingly white as ours in Ireland, though).

Boakye's previous book Black, Listed, was a sharp funny account (in list-form) of vocabulary in and about black British culture. In this one, he ranges widely across the education system as well as personal stories of his own 'odyssey', knitting both together powerfully:

Being black and being nice at the same is cause for frowns of concern... Niceness, as a proxy for white acceptability, becomes a mask that cannot slip and must not crack. And maintenance of this persona is akin to an ongoing trauma. It takes effort and premeditation; a constant pressure that goes unnoticed by the audience it is designed for.

Eat Or We Both Starve by Victoria Kennefick

is the arresting title of Victoria Kennefick's first full collection. It has, rightly, got plenty of attention: just a few days ago she won the Emerging Writer category in the Dalkey Literary Awards.

There is great variety of tone and form here, but always the language is close to the rawness of living - bodies, food, love, female experience, grief (there are very moving poems about her father). I'll pick out 'In Heptonstall' (Sylvia Plath's much contested grave) and another about a famous woman, 'Prayer to Audrey Hepburn', the last in the book:

I am conscious of my pudgy belly,

my rat's nest hair, but you take my face in your hands, kiss me hard,

pushing your gorgeous tongue across the length of mine,

Afterwards, our seams popping, we shriek with laughter.

Now that's the way to end a collection.

We Don’t Know Ourselves by Fintan O'Toole

Fintan O’Toole is one of Ireland's most perceptive commentators on public life. We Don't Know Ourselves stitches in a lot of personal material, and the result in a fascinating book which deservedly won the An Post Irish Book Awards Book of the Year in 2021. His central thesis is that for decades as a society we have both known what we are, and yet simultaneously tried to suppress that knowledge.

It's difficult to think of a European country which has changed so much over this time; I am slightly younger than O'Toole and remember all these public events, though seeing them through a slightly different filter, coming as I do from a different background to his urban (Crumlin) Roman Catholic one.

Coincidentally, one of the events he writes about, the Malcolm Macarthur murders in 1982 and subsequent political fall-out, are portrayed in a vivid new podcast from the Irish Times I've been listening to in recent days, GUBU: only 40 years ago, but a different country...

Spies in Canaan by David Park

David Park is an author I took a while to catch up with (especially considering that he used to be an English teacher), but have now often recommended. John Self recently interviewed him for the Irish Times.

I got a proof copy of his latest novel, Spies in Canaan, a few months ago, and now it's been published. The first part tells the story of the painful experiences of Michael, an American spy in Vietnam; the second, contemporary, part is surprising, still more painful, and very moving.

If you want to start on Park, I recommend first stop being his short novel Travellers in a Strange Land, my book of 2018, and described by Claire Kilroy in the Guardian as 'a short but breathtaking novel about parental heartache.' And then perhaps The Light of Amsterdam.

Seven Steeples by Sara Baume

Sara Baume now has an impressive corpus of four excellent books. I wrote last year about her recent non-fiction handiwork, and Seven Steeples has become her third novel to be published, after Spill Simmer Falter Wither and A Line Made by Walking. The central characters, Sigh and Bell (originally Simon and Isabel - even their names are reduced) confine themselves to poor isolated rural life, their only companions the dogs Pip and Voss, and over the years their lives become increasingly constrained. They are both almost totally disconnected (from 'the world') and totally connected (with each other, to the extent that they almost become one).

She writes beautifully, particularly about the natural world. Her books are strangely compelling, given how little 'happens'.

Cold Enough for Snow by Jessica Au

From the ever-reliable Fitzcarraldo Editions. This is from an author new to me. Just 94 pages long, it is told by a woman who has organised to meet her mother for a holiday in Japan. As they see the sights, thoughts go through her head about all sorts of things. It is elegant and elusive, and I enjoyed it. Don't expect much (overt) plot, though.

There is a memorable section in which the narrator and her mother visit the Church of the Light, designed by the architect Tadao Ando, near Osaka. Below, the extraordinary cross.

Dance Move by Wendy Erskine

is her second collection of short stories, following Sweet Home (2019). In Fortnightly 125 I recommended Bernard MacLaverty's top-notch Blank Pages, and now here is more evidence of the quality of current fiction-writing from Northern Ireland (MacLaverty has lived in Scotland for many years, though his stories are often set in NI). Think also of Anna Burns and her intense Booker-winner Milkman.

Erskine's stories are varied, funny, sharp. They often 'escalate' (à la George Saunders) in intriguing ways. John Self wrote a good review in The Critic.

Here's one you can read online: 'Nostalgie' is near the end of the book. Drew is invited to sing at the group of a reunion in Northern Ireland; he's rather enjoying his solo trip via ferry, unencumbered by family, but after he has performed things take a stomach-sickening turn.

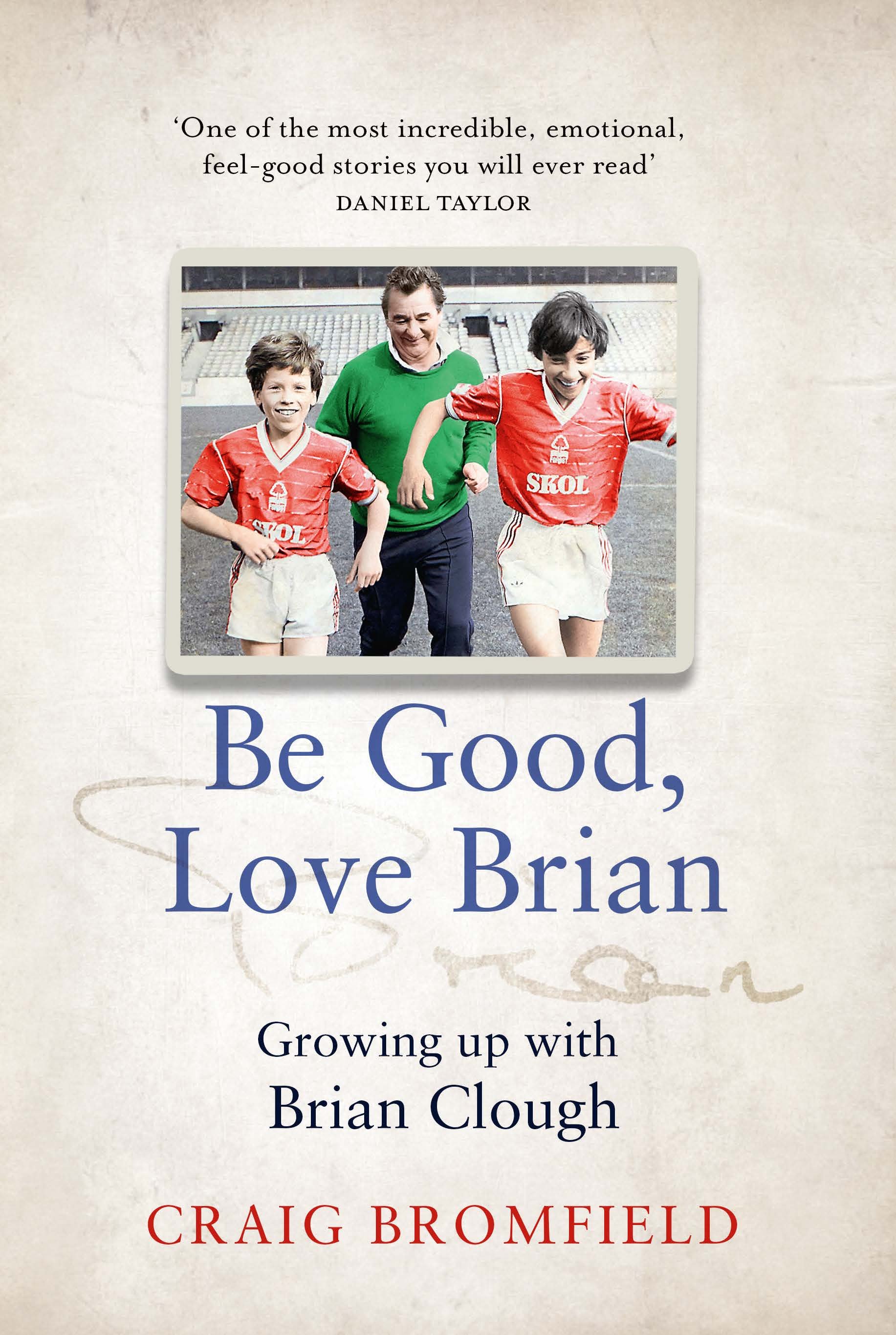

Be Good, Love Brian (Growing up with Brian Clough) by Craig Bromfield

I’m not claiming that this is high literature, but boy did I enjoy it. A lot of things came together for me: the time, the milieu, the football. Bromfield and his brother bumped into the Nottingham Forest squad on a beach near Sunderland in 1984, and over the succeeding years he became part of the Clough family, more or less moving into Brian and Barbara Clough's house in Derbyshire.

The arc of the story is both sweet and, eventually, sad (and if you follow football you will remember the disappointment of Clough's declining alcoholic years). Bromfield was interviewed in the Guardian here.

If this is your thing, you should also look at the wonderful documentary film I Believe in Miracles, the story of the European Cup triumphs engineered by Clough and Taylor.

Sea State: a memoir by Tabitha Lasley

I’m not sure I’m actually recommending this, since you'll have to be prepared for some raw experiences set in Aberdeen as the author interviews over 100 men about their experiences 'offshore' on the oil rigs. But there's no doubt it's memorable, sharply written, perceptive and sometimes funny.

The first man she interviews is Caden, a married man who becomes her lover, and an obsession. Like all offshore workers, he regularly heads into that mysterious all-male world in the brutal North Sea, a world which of course she never encounters herself, inversely-marooned as she is in the Scottish city.

Early on, Lasley boys a copy of Villages, and her sub-editor Tom warns her: 'He's not going to turn into John Updike. You know that, don't you?' Hardly a spoiler: indeed he doesn't.

Four Thousand Weeks: time and how to use it by Oliver Burkeman

4000 weeks is on average the time we are given on this planet. Oliver Burkeman's book makes you think deeply about the shocking shortness of this. The centre of his argument is we need fully to accept that we cannot accomplish everything that we want to (and most importantly should not even try), and we need to let go of that stressful expectation.

You can sign up to Burkeman's newsletter, The Imperfectionist, here.

Two thoughts from me:

As a teacher and a school leader (and I know there are lots of subscribers who are), this is well-worth reading. What really matters to us as we navigate the blizzard of demands on our time?

This Fortnightly is definitely something worth prioritising, even though I 'gain' nothing from it in immediate material terms. I wrote about that here.

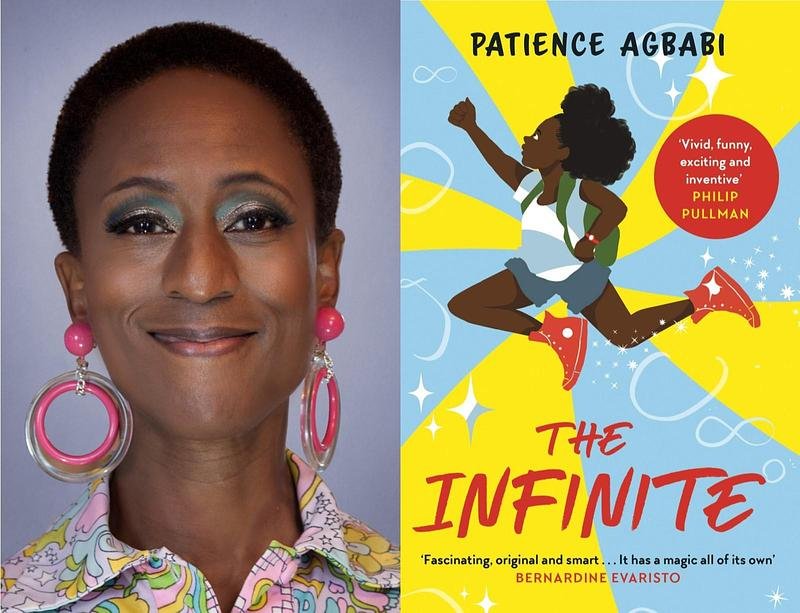

The Infinite by Patience Agbabi

A guest recommendation from my 10 year-old, in case you also know a child looking for a good read. She recommends the first book in this series (and is looking forward to the sequel, The Time Thief). A time-travel adventure, it features lots of lively characters, and is funny and unpredictable.

'It's SO good. It's so interesting.'

However, you definitely shouldn't read Agbabi's fabulous book Telling Tales to any children though. I wrote about it here. A contemporary version of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, it's extremely salty (and very funny).

My Phantoms by Gwendoline Riley

This was the first Riley novel I've read: very sharp and bracing. The section dealing with her car-crash father is funny, but the main relationship in the book is the narrator's with her mother, and at some stage in this short book you start to distrust the former, wondering about her attitude and even cruelty.

Mayflies by Andrew O’Hagan

This is very moving: the first half tells the story of the narrator and his friends as young men travelling from Scotland to Manchester for a carefree adventurous weekend of music. Jump forward decades, and he gets news of a terminal diagnosis for his best friend. The last part is - no real spoiler - set in Switzerland. Kenny Pieper has a good post on it here: 'While we once thought our lives would go on forever, we begin to realise that, like the Mayfly, our time here is very, very short.'

Conflicted: why arguments are tearing us apart and how they can bring us together by Ian Leslie

This is an accessible read for anyone who works in an institution (like a school), or a company, has personal relationships with others ... oh, right, so everyone then. His Substack, The Ruffian, is always interesting, perceptive and level-headed.

For the UK paperback edition, it’s been re-titled How to Disagree.