On Teaching Gerard Manley Hopkins

Forty-five years after I first encountered it, the impact of the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins is to me as explosive as ever. That first encounter was as a Leaving Certificate student: Augustine Martin’s famous poetry textbook Soundings had a small selection of poems that just burned off the page, starting with the amazing extended sonnet ‘That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire’:

Cloud-puffball, torn tufts, tossed pillows flaunt forth, then chevy on an air-

built thoroughfare: heaven-roysterers, in gay-gangs they throng; they glitter in marches.

His masterpiece ‘The Windhover’ (‘the best thing I ever wrote’), which I know off by heart, followed and then the touching ‘Felix Randal’; finally three darker sonnets, including the terrifying ‘No Worst, There is None’.

As a teenager why was I so thrilled by a poet with whom I have nothing in common in situation, nationality, belief or sexuality? The language of course: that extraordinary musical sweep of alliteration and assonance, of word-bending, word-coining, outrageous syntax, a kind of poetic equivalent of Van Gogh, verbal impasto. And also the sheer intensity - teenagers are intense, and Hopkins showed me how poetry could thrillingly transcend mere difference of circumstance or background. A few months ago I explained how I think that power makes poetry particularly important in the contemporary world.

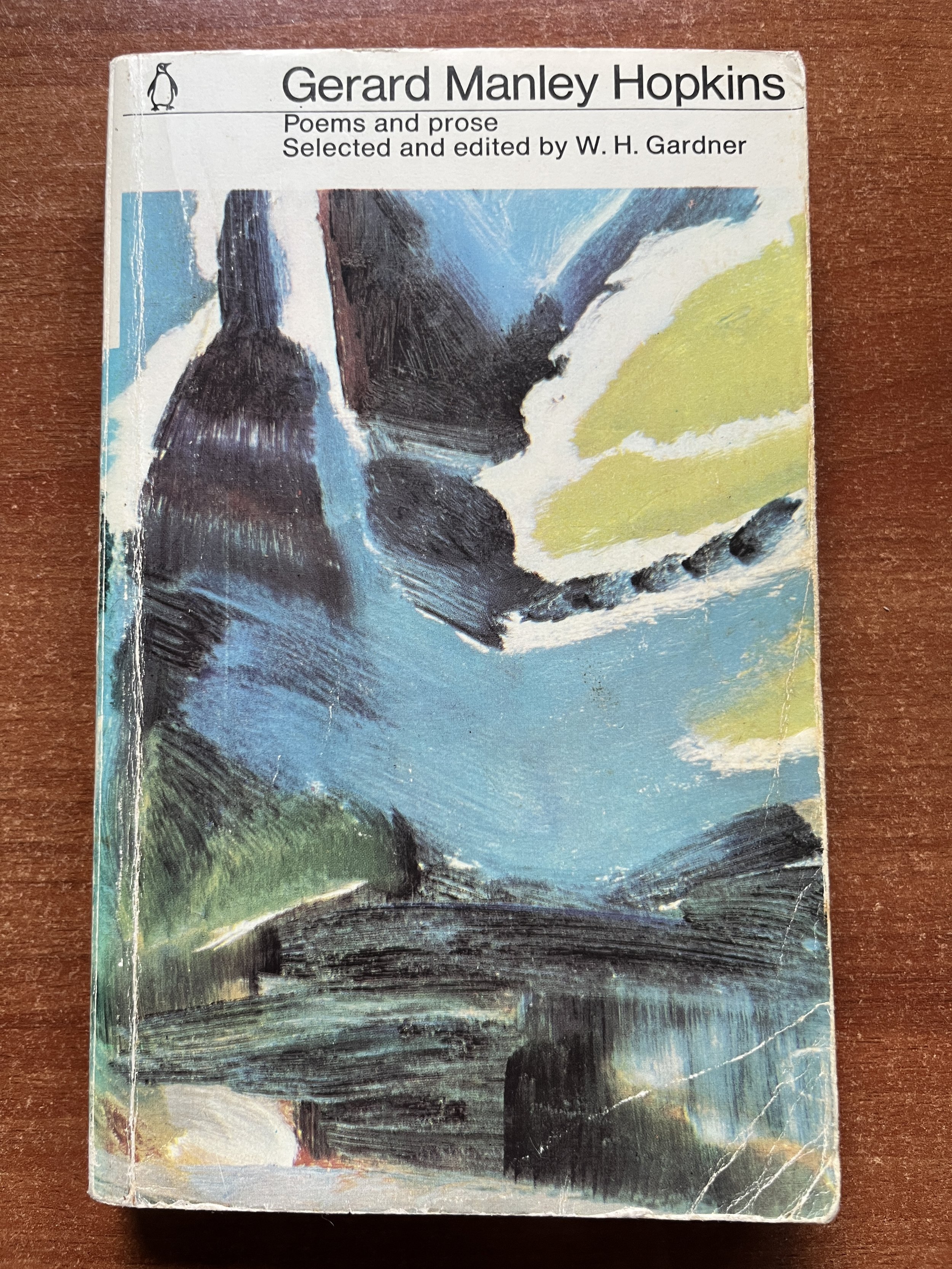

In the year after the Leaving Certificate my Hopkins horizons expanded to many of the other poems in the Penguin Poems and Prose edited by W.H. Gardner (pictured above: the cover art by Ivon Hitchens, ‘1960 First Variation’ was just right, but sadly it has been consigned to publishing history). At the start there is ‘The Wreck of the Deutschland’, a commemoration of the five Franciscan nuns drowned in 1875, with its arresting opening:

Thou mastering me

God! giver of breath and bread.

In 1979 my callow poem ‘Gerard Manley Hopkins’ was published in ‘New Irish Writing’ in the Irish Press under David Marcus, including those lines, and I also had a sequence of three sub-Hopkins sonnets published there.

In the Gardner edition there are a mere 53 completed poems, but all have that signature style: as I say to pupils, he is the one poet (perhaps accompanied by the poet before him in Soundings, Emily Dickinson) they will always be able to recognise instantly. There is the erotic charge of ‘Hurrahing in Harvest’, the yearning loss of ‘Binsey Poplars’, the agonised contortions of ‘Carrion Comfort’. Then just one-third of the way into the volume comes Section B, Prose, including diary entries and letters and, especially, selections from the Journals, a testing ground for observations of the natural world:

June 30 1866:

Thunderstorms all day, great claps and lightning running up and down. When it was bright betweentimes great towering clouds behind which the sun put out his shaded horns very clearly and in a longish way. Level curds and whey sky after sunset.

Seamus Heaney, in his essay ‘The Fire ‘i the Flint’ wrote that

His journals are scrupulous and slightly shocking evidence of the way his imagination was in constant, almost neurotic negotiation with his idea of the Creator.

Just so: both scrupulous and shocking, two words which capture the electric radicalism of a poet who was also deeply conservative.

When the new Leaving Certificate English course started over 20 years ago, it was wonderful that Hopkins was retained (on a carousel, not every year). It would have been easy to drop this awkward and seemingly outmoded figure from the Victorian era, but instead the selection was expanded, and now there are ten poems from ‘God’s Grandeur’ to ‘Thou art indeed just, Lord’, including the ecstatic ‘Spring’ and ‘Pied Beauty’, and I have recently been teaching him again. He ‘came up’ in our Mock examination, and may well do so in June’s paper. It is good that in this culture of fragmented attention and tendency to glib easy-ness we can spend time focussing on such a knotty, dense yet exhilarating writer. Most of the poems now on the course are sonnets, and no other poet in history has tested the limits of that form like Hopkins: his freewheeling playfulness with language in such a confined space is not a million miles from some musical forms teenagers access, and his focus on nature and its erosions is also very much of our time. A class spent on ‘The Windhover’ continues to be thrilling. You have to work hard on Hopkins: he takes you to demanding places, and this is just what young people should be opened up to.

And of course there is a local connection. The story of Hopkins’s work and life is one of divisions and contradictions: a radical writer who used conventional forms; an Anglican who became a Roman Catholic and then a Jesuit; a celibate who surely suppressed homo-erotic feelings; an Englishman who found himself in Ireland and plunged into despair, ending his life not in his homeland but instead, in his mid 40s, in Dublin. This most individualistic of writers was buried not in an individual plot but instead as ‘Gerardus Hopkins’ in the Jesuit section of Glasnevin Cemetery, 17 miles from where I write. Of course I have visited it: the photo shows my then-colleague John on a pilgrimage we made. Revisiting what Hopkins wrote continues to be cheering and sustaining, and introducing them to new generations remains a tonic.