On the Importance of Studying Poetry

Every now and then, to wind my pupils up a little, I ask them what they think is the most ‘important’ subject in school, and to justify their choice. Maths, History, Science, they say, and then, wearily, ‘I suppose we’re supposed to choose English, sir?’.

No, I retort, important though that is. Let’s be more precise: there is nothing more ‘important’ and indeed useful than…

Poetry.

Here, with only a soupçon of hyperbole, is why.

There is no more vital tool for us than language. Language is the foundation of all that we are as individuals, of human progress, of society itself, It is the foundation of all our relationships. Everything you do in life depends on using language at its more precise and most expressive. Therefore, in school, there is nothing more valuable than for you to learn how to use language as well as is possible, and only one subject does this. When you read and study poetry, you are looking at language at its most intense and deliberate. You are paying the closest attention to humanity’s greatest asset (and potentially its most damaging one).

As teenagers now, you are coming to adulthood in a world in which human attention is being relentlessly assaulted. You have fewer ‘places’ than anyone in history where you can concentrate and be with yourself. Largely through electronic media you are being overwhelmed by language from so many directions - from social media, manipulative politicians, and now artificial intelligence. Having the tools to consider what is true is so important for the life ahead of you, and being hyper-aware of how language works is the tool you need most.

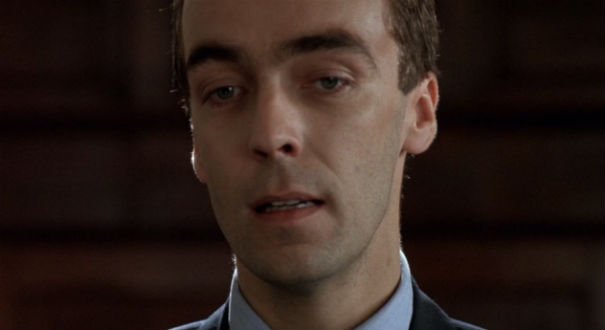

Poetry also deals with the most significant things in all our lives - falling in love, grief, nature, belief, identity. What other school subject approaches such significance? You may have noticed that at hinge moments in life people tend to reach for poetry: see the impact of John Hannah’s reading of W.H.Auden’s ‘Funeral Blues’ in the 1994 film Four Weddings and a Funeral (the grieving character starts with moving simplicity: ‘This is what I want to say’). In public statements at vital moments politicians often quote poetry to give their utterances more gravitas but also because poetry really does speak to people like nothing else. In Ireland, this usually means Seamus Heaney and W.B. Yeats. On Good Friday 2020 Taoiseach Leo Varadkar addressed the nervous nation about the seriousness of the COVID-19 situation and said this, referring first to the Northern Ireland conflict:

During the worst year of those Troubles the poet Seamus Heaney spoke about what was happening and predicted that ‘if we winter this one out, we can summer anywhere’ ... In one of his best collections of poems, Heaney celebrated the human chain of help that can bring about an almost miraculous recovery. As Heaney wrote, we were ‘all the more together for having had to turn and walk away’.

And early in the pandemic people were comforted by Derek Mahon’s poem ‘Everything is Going to Be All Right’ (here, Anthony Wilson in his wonderful collection Lifesaving Poems writes about it as a man who has had cancer, and who is facing other personal tragedies).

In the hurly-burly of the world we all need space, and spaces. When you are a teenager perhaps you need these all the more, as you try to come to terms with what you are and what you can be. Being outdoors is essential, away from screens: ideally schools provide you with opportunities to play sport and to spend time in the natural world. In any case, they can certainly provide such intellectual ‘space’ indoors. Studying a poem in class is an act of attention in a world of inattention (think of Elizabeth Bishop’s ‘The Fish’ which enacts such attention): just the words on a page, a teacher, a group of peers, attending together to the deepest things of life via the medium of the best words in the best order, as Samuel Taylor Coleridge defined poetry. You will be developing what Maryanne Wolf calls ‘cognitive patience.’ And when you are old and grey and full of sleep, and nodding by the fire, lines of poetry you read at school will come back to you, long after you have forgotten everything else from your studies.

Two examples from the last lines of well-known poems by Heaney:

‘A four-foot box, a foot for every year’ (‘Mid-Term Break’)

and

‘Next thing he spoke and I nearly said I loved him.’ (‘A Call’).

Pure simplicity: the power of those plain words box and nearly. Attending to and relishing such power is the value of the best discussions in class, when you can discover what truthful language can do. In the words of Julia Bell in her book Radical Attention:

Sometimes the best way to glimpse meaning is to start small, to pay attention to detail, and give your deliberate attention to what is in front of you. To try and notice what happens. You make time. To choose to look.

And if you do choose to look, where should you look? Ask your English teacher, who is bound to have good books to recommend. The poets I have named so far all come from the school curriculum in Ireland. You might also now have the opportunity to study the work of the challenging and provocative American poet Tracy K. Smith, and I will mention as well the poetry of John Donne, Shakespeare’s contemporary, which is often studied in the Leaving Certificate. But what value could an English clergyman from an utterly different culture 400 years ago have for a teenager now? Well, last year in her thrilling Super-Infinite: the transformations of John Donne (my book of 2022) Katherine Rundell showed us:

It was very deliberately that he wrote poems that take all your sustained focus to untangle them. The pleasure of reading a Donne poem is akin to that of cracking a locked safe, and he meant it to be so. He demanded hugely of us, and the demands of his poetry are a mirror to that demanding. The poetry stands to ask: why should everything be easy, rhythmical, pleasant? … The difficulty of Donne’s work had in it a stark moral imperative: pay attention. It was what Donne most demanded of his audience: attention. It was, he knew, the world’s most mercurial resource.

To turn to poets writing currently, as a sample I can recommend Victoria Kennefick’s Eat or We Both Starve, Molly Twomey’s Raised Among Vultures, Anthony Joseph’s Sonnets for Albert, Roger Robinson’s A Portable Paradise, James Harpur’s The Examined Life. What are these books about? Everything that matters - love, death, fathers, daughters, the body, being a woman, being a man, time, childhood, change. What you will experience will be the best-shaped thoughts of natural, rather than artificial, intelligence.

What could possibly be more important?

A revisiting of Thomas Newkirk’s book The Art of Slow Reading in the new AI world.